Journal of Tropical Oceanography >

Differences of sea surface temperature anomalies in the North Atlantic in springs of 1998 and 2016 and their causes

Received date: 2019-09-09

Request revised date: 2019-11-13

Online published: 2020-05-19

Supported by

National Natural Science Foundation of China(41575083)

National Natural Science Foundation of China(41730961)

Copyright

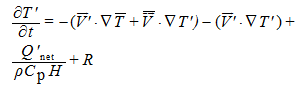

In this paper, we use reanalysis data and mixed layer temperature (MLT) budget analysis to study the differences of the North Atlantic sea surface temperature anomalies (SSTAs) between two Super El Niño (1997-1998 and 2015-2016) events and the causes for the differences. The results show that in the spring of 1998 the North Atlantic SSTA had clear positive, negative and positive distribution, while in spring 2016 it presented weakly negative, positive and negative distribution. The diagnostic results of factors influencing the SSTA in the tropical North Atlantic indicate that in the spring of 1998, in addition to the reduction of latent heat transferring from ocean surface to atmosphere and the increase in solar radiation absorption, the marine dynamic process, i.e., zonal Ekman drift, also played an important role. The thermal process was related to the negative phase of the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) that occurred after the peak of El Niño, which caused the Azores high pressure to weaken and generated southwesterly wind anomaly. The evaporation of the tropical North Atlantic was attenuated by the wind-evaporation-SST feedback mechanism. The eastward shift of the Walker circulation sinking branch also contributed to this warming. Different from the 1997-1998 El Niño event, the 2015-2016 El Niño event caused a weakly positive NAO phase instead of a negative one. The weak easterly anomaly in the tropical North Atlantic caused SST cooling; this may be the main reason for the significant difference between the North Atlantic SSTAs in the springs of 1998 and 2016.

XUE Wenjing , YU Jinhua , CHEN Lin . Differences of sea surface temperature anomalies in the North Atlantic in springs of 1998 and 2016 and their causes[J]. Journal of Tropical Oceanography, 2020 , 39(3) : 19 -30 . DOI: 10.11978/2019085

图1 1997—1998 (a)和2015—2016 (b)厄尔尼诺事件的Niño3.4(5°S—5°N, 170°—120°W)异常指数及北大西洋三极型异常指数的演变月份后的0表示发展年份, 1表示衰减年份 Fig. 1 Anomalous Niño 3.4 (170°-120°W, 5°S-5°N) index (dotted line, left axis), anomalous North Atlantic tripole mode index (solid line, right axis) evolution during El Niño events of 1997-1998 (a) and 2015-2016 (b). The number 0 represents a developing year, and 1 represents a decaying year |

图2 厄尔尼诺发展阶段(a—d)、峰值阶段(e、f)和衰减阶段(g—j)的850hPa风异常及SSTA分布方框分别代表北大西洋三极指数NATI的三个区域; a、c、e、g、i为1997—1998厄尔尼诺事件; b、d、f、h、j为2015—2016事件 Fig. 2 SSTA (shading) and anomalous wind vector at 850 hPa (arrow) during the developing phase in June-August (a, b) and September-November (c, d), the peak phase in December-February (e, f), and the El Niño decaying phase in March-May (g, h) and June-August (i, j) for 1997-1998 (left panels) and 2015-2016 ( right panels) |

图3 海洋动力过程(绿色)和热力过程(橘色)对1998和2016年3月与1月热带北大西洋(10°—25°N, 50°—15°W)区域平均海洋混合层海温异常变化(灰色)的贡献Fig. 3 Ocean dynamic process (green) and thermal process (orange) contributions for the change of regionally-averaged ocean mixed layer SSTA (gray) in the tropical North Atlantic (50°-15°W, 10°-25°N) in January-March of 1998 and 2016 |

图5 厄尔尼诺发展阶段(9月)至衰减阶段(8月)期间热带北大西洋海域的表面风异常和潜热通量异常(等值线, 单位: W·M-2, 热量以向海洋输送为正)及SSTA经向时间剖面结构各量均为热带北大西洋(50°—15°W)的区域平均, 等值线实线为正值, 虚线为负值; a为1997—1998年; b为2015—2016年 Fig. 5 Meridional time section structure of the tropical North Atlantic surface wind anomaly (arrow; units: m·s-1), latent heat flux anomaly (contour; units: W·M-2, downward is positive), SSTA (shading; units: ℃) from September in El Niño developing phase to August in El Niño decaying phase. All data are regionally-averaged in the tropical North Atlantic (50°-15°W). The solid line is positive and the dashed line is negative. a) 1997-1998; b) 2015-2016 |

图6 热带北大西洋在2月份表面潜热通量异常(a、b, 单位: W·M-2)、表面净短波辐射异常(c、d, 等值线, 单位: W·M-2)和1—3月覆盖总云量的异常值(c、d, 阴影, 单位: %)的空间分布等值线实线为正值, 虚线为负值; a、b的等值线间隔为10, c、d的等值线间隔为4; 方框为热带诊断区; a、c为1997—1998厄尔尼诺事件; b、d为2015—2016事件 Fig. 6 Spatial distributions of tropical North Atlantic surface latent heat flux anomaly (a, b; units: W·M-2), net surface shortwave radiation anomaly (c, d; units: W·M-2) in February and the anomalous total cloud cover (c, d; shading, units: % ) in January-March in El Niño developing years. The solid line is positive and the dashed line is negative, Contour lines range from -60 to 60 with an interval of 10 (a, b) and range from -16 to 16 with an interval of 4 (c, d); Boxes are tropical diagnostic area. (a, c) are for 1998, and (b, d) are for 2016 |

图7 厄尔尼诺衰减年1—3月太平洋、大西洋区域500hPa的位势高度异常(等值线, 单位: gpm), 对流层温度异常(阴影)和850 hPa风异常(箭头)的空间分布等值线实线为正值, 虚线为负值, a. 1998年; b. 2016 Fig. 7 Spatial distributions of Pacific and Atlantic anomalous geopotential height at 500 hPa (contour; units: gpm), anomalous tropospheric temperature (shading; units: ℃) and anomalous wind vector at 850 hPa (arrow; unit:s m·s-1) in Jannuary-March in El Niño developing years. The solid line is positive and the dashed line is negative. a) 1998; b) 2016 |

图8 厄尔尼诺衰减年太平洋、大西洋区域1—3月300hPa纬向风异常的空间分布a. 1998年; b. 2016年; 等值线为气候态(单位: m·s-1) Fig. 8 Spatial distributions of Pacific and Atlantic anomalous zonal wind at 300 hPa (shading; units: m·s-1) and climatology (contour; units: m·s-1) in Jannuary-March in El Niño developing years. a) 1998; b) 2016 |

图9 厄尔尼诺衰减年1—3月大西洋区哈德莱环流异常区域(80°W—0°)内平均的经向辐散风(单位: m·s-1)与垂直速度异常的经向垂直剖面结构(a、b, 单位: 10-2mb·s-1)及Walker环流异常区域(5°S—5°N)内平均的纬向辐散风(单位: m·s-1)与垂直速度异常的纬向垂直剖面结构(c, d, 单位: 10-2mb·s-1)a、c. 1998年; b、d. 2016年; 箭头表示两个矢量的合成 Fig. 9 Meridional vertical section structure of Hadley circulation anomalies in the Atlantic (between 80°W and 0°) by averaging anomalous longitudinal divergent wind (a, b; units: m·s-1) and anomalous vertical velocity, zonal vertical section structure of Walker circulation anomalies (between 5°S and 5°N) by averaging anomalous latitudinal divergent wind (units: m·s-1) and anomalous vertical velocity (c, d; units: 10-2 mb·s-1) during El Niño developing phase in January-March. (a, c) 1998; (b, d) 2016 |

| 1 |

杜美芳, 徐海明, 周超 , 2015. 基于CMIP5资料的热带大洋非均匀增暖及其成因的分析[J]. 热带海洋学报, 34(3):1-12

|

| 2 |

李刚, 李崇银, 江晓华 , 等, 2015. 1900~2009年全球海表温度异常的时空变化特征分析[J]. 热带海洋学报, 34(4): 12-22.

|

| 3 |

李晓燕, 翟盘茂 , 2000. ENSO事件指数与指标研究[J]. 气象学报, 58(1): 102-109.

|

| 4 |

刘珊, 王辉, 姜华 , 等, 2013. 北太平洋海表温度及各贡献因子的变化[J]. 海洋学报, 35(1): 63-75.

|

| 5 |

任宏昌, 左金清, 李维京 , 2018. 1998年和2016年北大西洋海温异常对中国夏季降水影响的数值模拟研究[J]. 气象学报, 75(6):877-893.

|

| 6 |

薛峰, 段欣妤, 苏同华 , 2018. 强El Niño衰减年东亚夏季风的季节内变化: 1998年和2016年的对比分析[J]. 大气科学,42(6):1407-1420.

|

| 7 |

郑依玲, 陈泽生, 王海 , 等, 2019. 2015/2016年超强厄尔尼诺事件基本特征及生成和消亡机制[J]. 热带海洋学报, 38(4):10-19.

|

| 8 |

|

| 9 |

|

| 10 |

|

| 11 |

|

| 12 |

|

| 13 |

|

| 14 |

|

| 15 |

|

| 16 |

|

| 17 |

|

| 18 |

|

| 19 |

|

| 20 |

|

| 21 |

|

| 22 |

|

| 23 |

|

| 24 |

|

| 25 |

|

| 26 |

|

| 27 |

|

| 28 |

|

| 29 |

|

| 30 |

|

| 31 |

|

| 32 |

|

| 33 |

|

| 34 |

|

| 35 |

|

| 36 |

|

| 37 |

|

| 38 |

|

| 39 |

|

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |